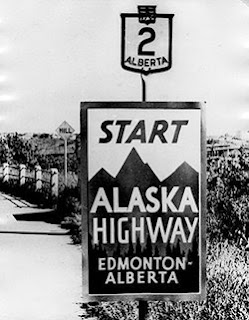

Some writing gigs are a pure horror. One such horror was this, a young adult non-fiction book about the building of the Alaska Highway (very short version: authorized right after Pearl Harbor to link North American air bases through U.S., Canada, and Alaska, the highway was begun in February 1941 and finished, 1600 miles later, in September 1941, an engineering marvel spearheaded by the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers). I don’t know why. I love history and usually like this stuff. But I plowed through and now that it’s done, I think it came out okay:

Work Until You Drop

Yet as with all other obstacles faced along this road, the soldiers could do nothing but keep working, twenty-four hours a day, seven days a week, “We were working, I think, eight-hour shifts. Three eight-hour shifts,” said General Hoge of the official schedule that had been set down for his crews, but the reality in the field was often quite different … and exhausting. Henry Geyer was a truck driver with the army engineers who recalled this hard duty on “Building the Alaska Highway,” saying simply, “You worked until you dropped.” But, he added, “You had to do the job. You didn’t like it. So you figured that you might as well as enjoy it, because otherwise you’d have gone nuts.”

Bob Batey, another engineer interviewed on the (PBS) documentary, agreed. “In the summer, the sun was up all the time,” he said, offering impossibly long 20-hours of sunlight at their northern location. “We were on 12-hour shifts. Half of the company was in the morning, and half at night. We worked all the time, seven days a week.”

“It was slave labor, is what it was,” said Wallace Lytle. “We weren’t prisoners, but wanting to get the job done, we’d done most anything to do it.”

ay their heads pretty much wherever they fell. “We was working so hard that by the time you got through at night, you rolled your sleeping bag out underneath a tree or in the bushes, and you crawled in it and sacked out,” said Chester Russell, a former rodeo worker from California and no stranger to hard work.

Alden Hacker was another engineer who vividly recalled the exhaustion that daily overcame these workers. “Seldom did we ever put a tent up and tie all of the corners together. Usually you put them up and just enough to hold them together, because they’re only going to be there for the night. The next day, the cooks would have to tear them down, load them up, and move them up the road as close to the front as they could move.”

“We worked twelve and fourteen hours a day in the rain and the flies and the mosquitoes made life miserable for us, particularly in the open mess camps,” remembered Master Sergeant George H. Burke of the 95th Engineers in The Alaska Highway. “We had hardly any free time, and most of what we did have we spent playing cards or pitching horseshoes.”

Everyone suffered from the combination of cold and lack of sleep. Mistakes were common and accidents frequent. While damaged vehicles and machines could be towed to the nearest camp for repairs, there were not enough tow trucks and spare parts to keep up with the demand. Wrecks were left to accumulate on the side of the road and, against Army regulations, some wrecks would be stripped of spare parts to be used in the repair of other vehicles. According to one witness, “each temporary base cap began to resemble a military junkyard.”

Soldiers went for long stretches with no other company that that of their comrades and, though often overcome with exhaustion after the long day’s labors, they keenly felt the isolation. On “Building the Alaska Highway,” army engineer Chester Russell said, “There was nobody. There was absolutely nobody. As far as young sweetie pies up there … we never seen a lady.” Fellow engineer William Griggs agreed, recalling “We were completely isolated in most cases. At the beginning we were near some Indian villages, but most of the time we were completely isolated.” Despite the hardships, isolation and loneliness, the soldiers understood all too well the importance of the task they had been assigned.

Occasionally, movies would make their way out to some of the camps where men like Burke, who had been a Washington, D.C. film projectionist before he was drafted, who show them on the 16-millimeter projector. Even rarer were visits by USO (United Service Organizations) shows, a charitable, non-profit organization which provides entertainment and recreation to U.S. military stationed the world over. One such show featured violin virtuoso Yehudi Mehuhin in concert in Whitehorse.

But such diversions were few and far between for the men of the Alaska Highway. An article in a 1942 issue of Engineering News Record put the situation in perspective: “There was no recreational program provided for soldiers or civilians, probably none could have been provided. Work, work, work, and more work was the only program – day and night, seven days a week.”

An article in the New York Times from December 31, 1942 said, “The boys who built the Alcan highway … (are mostly) drafted youth from the corners of America, they do not like to be told now that they are heroic, for their job held no glamour for them. They met it with curses and sweat. But with only their endless work, and their beefs, their checkers and their profanity for amusement they have pounded a road from the outpost of the outside world at Dawson Creek straight through to the heart of Alaska. They have done it despite hell, high water, and above all, loneliness. Many of them are eager to get out of Alcan country and into actual battle. But perhaps no action can be more dramatic or demanding than that which they have faced.”

More important than comfort, convenience or entertainment was speed.

Keeping the troops fed was another problem for the workers scattered along the length of the Alaska Highway. Engineers and workers would often not see fresh food for months at a stretch, relying instead on so-called C-rations, or prepackaged meals which offered few options, usually vegetable hash, meat hash, and chile con carne. But the limited menu soon had the soldiers resorting to the age-old practice of bartering with the locals for some relief from their steady diet of prepared canned meals. “We got so sick and tired of the chili con carne, we would send truckloads of chili con carne down to the Indian village and trade it off for fish” recalled engineer William Griggs. “And they said, ‘We’ll trade, but no more chili con carne.’ They got tired of it, themselves.”

“We lived on Spam and Vienna sausage,” said Fred Mims, while Chester Russell recalled, “Pancakes … was the number one on the list. Pancakes. We ate pancakes three times a day there for about a month.”

The New York Times article of December 31 described the conditions found in a typical camp: “Potatoes are iron-hard and have to be thawed for many hours before they can be cooked. Pancake batter may be freezing on top, and burning where it touches the stove. Returned laundry arrives in a solid chunk, which has to be set beside the oil drum stove for days before a sock or a handkerchief can be pried loose … At all times the cold is the omnipresent factor, it is cruel to both men and machines.”

Time Magazine reported that “Out in the bush the only recreation is hunting and fishing … (soldiers) hunt to vary meals of corned beef, potatoes, lemonade, carrots, preserves and dried eggs, by adding moose and bear steaks, lake trout, spruce partridge (Yukon chickens), ptarmigan (a species of game bird), grouse, venison. At Swan Lake, for lack of regular (fishing) tackle a Signal Corps man made a line from telephone wire, hammered a fishing spoon out of a tin can and brought in strings of fat trout over the side of an assault boat.”

African-American Soldiers

African-American soldiers were thought to be especially vulnerable to the cold and harsh conditions they were to face up north. Shockingly, the official U.S. Army position, as put forth by a study made by the Army War College, a training school for military officers, was “The Negro is careless, shiftless, irresponsible and secretive … He is best handled with praise and by ridicule.”

Indeed, the military was reluctant to even send African-American troops to work on the highway for fear that they would not be able to keep up with their white counterparts on this vital and fast-moving project.

It was, in fact, unofficial army policy to not send African-American troops places like Alaska and Canada because of the mistaken assumption that they were not capable of performing well in the extreme cold. But a wartime shortage of troops right after the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor and before draftees and enlistees could be trained and shipped out forced the use of the black troops on this vital northern mission. Though making up about one-third of the troops assigned to the highway, the African-American soldiers were more often than not assigned the harshest jobs under the worst conditions, including laboring on the brutal CANOL pipeline project. They were used only because the better-trained and equipped whites were needed for jobs deemed more important. Yet the black workers were routinely under-equipped and little thought was given to their physical well-being or safety. It was not unusual for supplies and equipment to go to white soldiers, leaving the African-Americans to make do with hand tools, laboring for weeks at a stretch in brutal temperatures that could reach -60º F for weeks at a time, living on frozen rations and in drafty canvas tents.

“Blacks in uniform had to endure the Army’s discriminatory racial policies,” said historian Heath Twichell. “The frequent expressions of hostility and contempt they encountered from individual whites only made that experience all the more painful.”

For the African-Americans working under white officers trained under these prejudicial beliefs, conditions were even tougher than those faced by white soldiers. According to Twichell, “In the minds of most senior white officers, black troops were not as capable in terms of their technical efficiency and ability to use the equipment. There was an expectation that they would do poorly.” All their work and their every action were a test to prove to the white officers and soldiers that they were as capable as anyone else to get the job done

Of course, as was ultimately proven by such examples as the durability of the construction of the 300-foot (91 meter) Sikanni Chief River Bridge by African-American regiments in less than four days and their records for most mileage built, the army vastly underestimated the intelligence and skill of their black soldiers.

Tags: Alaska, Chelsea House, Facts On File, Highway, non-fiction