When I was a kid, my heroes were astronauts.

I didn’t care for or follow sports, the country wasn’t, at the moment, engaged in any wars, and I knew that the heroic figures I saw in movies and on television weren’t real. But starting in 1961, America, and six year old me, had NASA’s Mercury Seven to inspire and awe.

Their names and faces were as familiar to me as the cast of Captain Kangeroo: Walter M. Schirra Jr., Donald K. “Deke” Slayton, John H. Glenn Jr., Scott Carpenter, Alan B. Shepard Jr., Virgil I. “Gus” Grissom and L. Gordon Cooper. They were the clean-cut ideal of the era, cocky, courageous, cool…you could just see them, throwing back a few Heinekens with JFK, Frank, and the Rat Pack around the pool. Philip Kaufman’s The Right Stuff really comes close to evoking the excitement, magic, and craziness of the time.

I worshipped them all. I was glued to my television for every Mercury, Gemini, and Apollo mission, from Alan Shepard’s first sub-orbital flight…and past Apollo 17, on to the first flight of the Space Shuttle in 1981. I read everything I could about space flight and the astronauts, collected toy space capsules and lunar landers, and made spacesuits and space capsules for my G.I. Joe.

My favorite was John Glenn (July 18, 1921). He was tailor-made for the role of All-American hero, the one the other astronauts called the “clean Marine,” and I was ripe for a hero to worship. The other kids liked Mickey Mantle or Frank Gifford for…what? Catching or hitting a ball? Please! John Glenn won five Distinguished Flying Crosses…before riding a rocket into outer space and orbiting Earth!

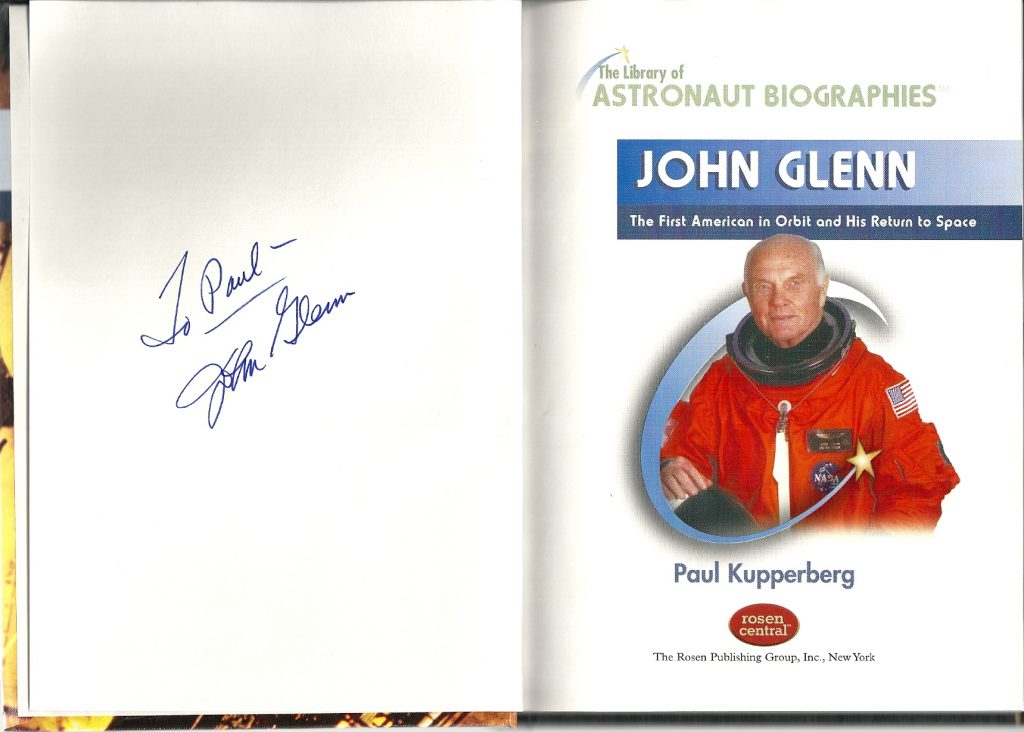

In 2003, I was offered the assignment of writing one of the books in Rosen Publishing’s The Library of Astronaut Biographies, one of their many young readers series for the school library market. The editor sent me a list of the available titles and I immediately called dibs on John Glenn, who had famously made his second voyage into space thirty-six years after his first, at the age of 77.

After John Glenn: The First American in Orbit and His Return to Space was published, I sent two copies to (by then) ex-Senator Glenn’s office in New Concord, Ohio; one I inscribed to him, the second with a SASE and a request for his signature. A few weeks later, this arrived in my mailbox:

Introduction: Something in the Air

Introduction: Something in the Air

The United States of the 1920s was a nation celebrating its newfound position of importance on the world stage. Strengthened by a turn-of-the-century military expansion to face challenges in places like Cuba, the Philippines, Panama, China, and Honduras, fresh from victory in the first World War, America was stronger than it had ever been, militarily and economically.

In that decade of unlimited potential, the exuberant “Roaring Twenties,” aviation was a craze and aviators its heroes. It was fueled by tales of the exploits of such World War I aces as America’s Captain Eddie Rickenbacker and Germany’s Oberleutnant Lothar Freiherr von Richthofen. It was fed by air shows and countless barnstormers crossing the country, selling excitement and rides in their airplanes. The sky was the new frontier, in need of exploration and taming, with aviation pioneers like Glenn Curtiss, Lincoln Beachey, Charles Lindbergh, Amelia Earhart, and Billy Mitchell, and early air mail pilots with names like Askew, Neville, Garrison, and Johnson leading the way.

Long before Ohio bicycle repair shop owners Orville and Wilbur Wright made the first powered flight in a heavier-than-air machine at Kitty Hawk, North Carolina on December 17, 1903, mankind had been fascinated by the idea of flying. From the winged angels of Biblical times and the Greek myth of Icarus, to the 15th Century drawings of manned flight by artist and inventor Leonardo Da Vinci and the 19th Century craze for lighter-than-air balloons, man has always longed to take to the skies. The Wrights showed the world man could fly, and in the decades to come, the airplane would evolve from the first, simple 750-pound open-framed craft powered by a twelve-horse power gasoline engine to its sleeker, vastly more powerful modern form.

While the 1920s is considered a Golden Age of Aviation, it was the infancy of another mode of airborne transportation: rocketry. The world over, young men turned their sights towards the heavens above the skies ruled by propeller-driven aircraft. Aerospace pioneers like America’s Robert Hutchings Goddard, Russia’s Konstantin Eduardovitch Tsiolkovskyand, and Germany’s Hermann Oberth were building a launch-pad of knowledge that would, one day, send mankind thundering into outer space atop giant, fire breathing engines of unimaginable power.

But before that would happen, a generation would come of age. A generation weaned on aviation, growing up alongside the advent of regular air mail routes, scheduled airline passenger service, and landmarks of aviation such as Charles Lindbergh’s 1927 solo crossing of the Atlantic Ocean. They would reach maturity in a world war that saw military air power come into its own.

And it was one of that number, born in 1921 in Ohio, birthplace of the Wright Brothers, who would become the very symbol of the best and brightest that generation had to offer. As a pilot, he was a decorated ace in two wars and a test pilot of distinction. As an astronaut, he was the first American to orbit the Earth. He was a successful businessman before serving twenty-four years in the U.S. Senate, once running for president. As a 77-year old senior citizen he again underwent the rigors of astronaut training and returned to outer space aboard the space shuttle Discovery.

John Glenn’s life has been one of dedication, courage, and service, its path shaped by patriotism and determined by an idyllic upbringing in a time and place when the world was speeding higher and faster through the skies than anyone had ever dared dreamed possible.

# # #

Conclusion: “A Joyous Adventure”

In 1995, Senator Glenn was reviewing materials for an upcoming debate on funding for the international space station. In the course of this, he read Space Physiology and Medicine, a book written by three NASA doctors, which listed “fifty-two different types of physical changes that happen to astronauts in orbit.” The list included balance disorders, osteoporosis, disturbed sleep patterns, cardiovascular changes, and many others…all of which the seventy-three year old legislator and veteran of the Special Committee on Aging recognized as similar to the effects of aging on the elderly. Why that was, and what effect (and after effect) space flight might have on the elderly, were questions that occurred to John. He thought such information could be applied to help astronauts better endure space flight, as well as offering some insights into reversing the effects of aging.

Believing these questions warranted further investigation, John spoke with the NASA doctors who wrote the book, as well as a variety of experts in geriatric medicine. It seemed to the senator that with the regular schedule of space shuttles being flown, surely there was room for experiments in this area…experiments he, himself, might conduct!

In the course of regular budgetary meetings with NASA director Dan Goldin, John began pitching both his scientific mission and his reasons to be the one to fly this particular mission. He even pressed his agenda with President Bill Clinton, who would have to approve any mission John might take, in Ohio on a 1996 campaign stop.

On February 20, 1997, John took the opportunity of the thirty-fifth anniversary of his historic space flight to announce his intention to retire from the Senate at the end of his current term. He was seventy-six years old and had lead an amazing life. He had proven successful in not one, or even two, but four different careers over the course of his lifetime, from pilot to astronaut to businessman to politician.

But retirement didn’t mean John Glenn was ready yet to settle down. He decided he still had one more job to do.

# # #

John Glenn knew from the start that he would have an uphill battle convincing NASA to give him a seat on the shuttle. First, he needed to be sure he was physically up to the challenge, and, second, that the mission he was proposing was scientifically valid. He insured the first by putting himself through as thorough a physical examination as he had ever undergone, including “every heart exam known. I went through liver, kidney, and pancreatic scans, a whole-body MRI, and one for my head alone.”

With reassuring results, John met again with NASA director Goldin and pitched his scientific program. Goldin agreed to review John’s proposal and sent him to the Johnson Space Center to undergo the same physical and tests that any astronaut would be required to take before being cleared for flight. John already knew that the NASA doctors would give him a clean bill of health. The scientific review board did the same for John’s experimental agenda. A news conference on January 16, 1998 made it official: John Glenn was going back into space!

He was assigned to the crew of the space shuttle Discovery as a payload specialist on mission STS-95, a nine-day flight scheduled to launch October 29.

The announcement set off a furor within the press that reminded John of his days as one of the Mercury Seven. One of the first men in outer space, America’s first man in orbit, John was now almost twice the age he had been for his first flight. He was, once again, in the spotlight, and though he could not deny the thrill of finally, all these years later, making his second flight, he was genuinely excited about the science he would be conducting in orbit.

The experiments would focus on several areas where the aging process and space flight experience share a number of similar physiological responses, including bone and muscle loss, balance disorders, and sleep disturbances to better understanding the basic mechanisms of aging. The physiological changes that occur in space (cardiovascular deterioration, balance disorders, weakening bones and muscles, disturbed sleep, and depressed immune response) reverse themselves following an astronaut’s return to Earth. Discovering why might help science discover how to reverse the same conditions in the earthbound elderly.

John was the perfect “guinea pig” for orbital experiments in aging. “We have 42 years of medical history on Senator Glenn and we were able to perform an exhaustive medical evaluation,” said Dr. Denise Baisden, a NASA flight surgeon. The ability to make comparisons between his responses to space flight in 1962 and then again, thirty-six years later, was unparalleled. “Senator Glenn is particularly well qualified since he has done this before,” said Dr. Robert Butler, professor of Geriatrics at Mount Sinai Medical Center, and a part of the Geriatric assessment team. “His involvement makes a bold statement about the capabilities of older people and will help us understand the effects of aging and space flight.”

John joined a team as elite as the original, first class of astronauts. He would fly with mission commander Lieutenant Colonel Curtis L. Brown, Jr. (USAF), pilot Lieutenant Colonel Steven W. Lindsey (USAF), Mission Specialist-1 Stephen K. Robinson (Ph.D.), Flight Engineer and Mission Specialist-2 Dr. Scott E. Parazynski (M.D.), Mission Specialist-3 and European Space Agency (ESA) astronaut Pedro Duque, and payload specialist Dr. Chiaki Mukai (M.D., Ph.D.) from the Japanese Space Agency (NASDA).

John was able to hold his own against his far younger crewmates. The ex-jet jockey had never stopped flying his own plane. He found the physical exercise “demanding but fun,” but then he had never let lapse his daily regiment of running (later power walking) and training with free weights that he had begun during his first stint as an astronaut. He once again rode the centrifuge, although at half the G-force he had experienced in his Mercury days. The space shuttle provided a far gentler lift-off and reentry than had his old Atlas rocket.

And, in order to establish an Earthbound baseline of his physical condition to compare to the results of the orbital experiments, he was subjected to as exhaustive a battery of medical tests as can be imagined, finding himself scanned, poked, prodded, and analyzed and giving endless samples of blood and urine and any other bodily fluid they could think of taking. To study his sleep patterns, John swallowed a “pill” that contained a thermometer and transmitter to record his core body temperature.

On October 29, 1998, payload specialist John Glenn rode the space shuttle Discovery on its over seven million pounds of thrust, back into outer space. This journey would last almost nine days, taking the septuagenarian senator some 3.68 million-miles in 134 orbits, and yielding results in his orbital experiments that are still being studied. Yet John Glenn had already flown farther, higher, and faster than he had ever dreamed possible for anyone. His contributions have been recognized the world over, no where more so than at home, where the New Concord High School was renamed in his honor, while Muskingum College now features the John Glenn Gymnasium, and Highway 83 where his boyhood home was located is now called Friendship Boulevard, and the stretch of Interstate 40 between his birthplace in Cambridge and his home in New Concord has been designated John H. Glenn Memorial Highway.

And even his successful return to space at the age of seventy-seven didn’t signal John’s retirement. He is an honorary member of the International Academy of Astronautics, an inductee to the Aviation Hall of fame and National Space Hall of Fame, a member of the Society of Experimental Test Pilots, Marine Corps Aviation Association, Order of Daedalians, National Space Club Board of Trustees, National Space Society Board of Governors, International Association of Holiday Inns, Ohio Democratic Party, State Democratic Executive Committee, Franklin County (Ohio) Democratic Party, 10th District (Ohio) Democratic Action Club, and 33rd Degree Mason, elder of the Presbyterian Church, on the Muskingum College board of trustees, and participant in numerous charitable causes.

In 1998, John donated his papers to The Ohio State University, forming the John Glenn Institute for Public Service and Public Policy. The Institute, and Senator Glenn, remains active in interesting students of all ages in their communities, preparing them for leadership, and inspiring them to take part in active citizenship and enhancing the quality of public service.

But to two generations, to the children of 1962 and 1998, the name John Glenn conjures the smiling image of an heroic figure clad in a high-tech space suit, ready to take the next step into the unknown. And, to John Glenn, the step from his first, brief flight in an open cockpit, single-engine plane in 1929 to his nine-day voyage aboard the very cutting edge of aerospace technology almost seventy years later must truly seem like the greatest leap of all.

Tags: Apollo, astronauts, biography, Gemini, John Glenn, Mercury 7, NASA, Rosen Publishing