“Those who cannot remember the past are condemned to repeat it.”

George Santayana

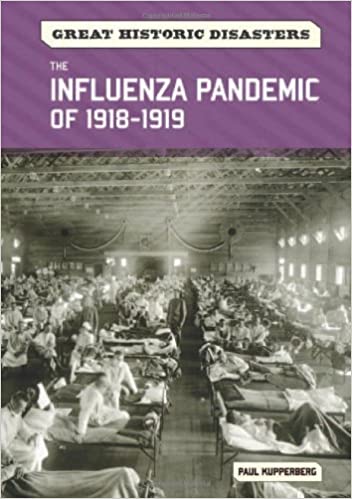

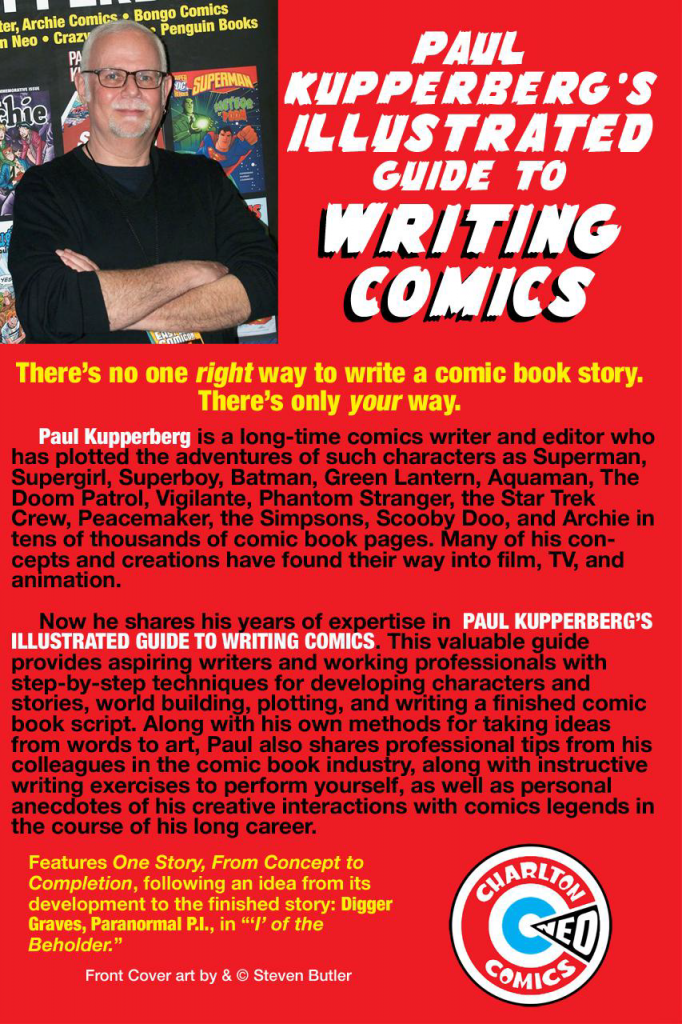

In the early 2000s, I wrote several nonfiction books for middle school/high school readers for Rosen Publishing. These slim books, typically 12,000 – 25,000 words each, were volumes in series for school libraries, like “Astronaut Biographies” or “Histories of the American Colonies,” or this one, “Great Historic Disasters.” I imagine there have been hundreds of bad school reports cribbed from the fourteen books I wrote for Rosen (and later, Chelsea Publishing).

This one seems relevant for the current times.

Great Historic Disasters

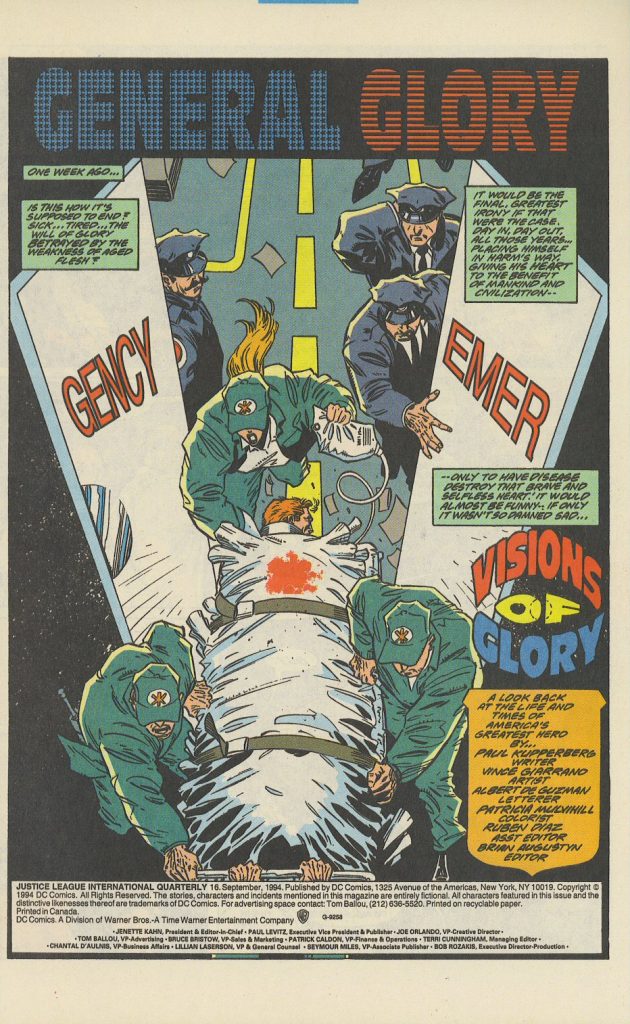

by Paul Kupperberg

1st Draft: 4/8/07

(23,120 words)

Introduction: “Influenza of a Severe Type”

When Dr. Loring Miner came to Haskell County, Kansas in 1855 after graduating from Ohio University, the science of medicine was still struggling to gain footing amid thousands of years of accumulated knowledge of healing based on well-meaning but faulty premises of the nature and causes of disease. Many believed, in this era only a decade before the Civil War, that illness was caused by “miasma,” or foul emanations from soil, air, and water. These emanations created an imbalance of what was known as the four “humors,” or fluids; yellow bile (urine), black bile (feces), blood, and phlegm (saliva). Too much of one or not enough of another caused various health problems which, doctors believed, could be cured by, among other methods, inducing vomiting or bleeding the patient to restore harmony.

The true cause of illness, known as the germ theory

of disease which states that disease is caused by microorganisms which infect

the body from outside through the air or through contact with infected

individuals. was just beginning to gain slow acceptance in the medical

community. It would not be until the last quarter of the 19th

century that the old theories would finally be discarded with the discovery of

microorganisms as the true carriers of disease.

But even with acceptance, few tried and true medicines existed to prevent or cure disease. Vaccination, the introduction of a small dose of a disease into the body to force it to develop disease-specific antibodies and immunity to that disease, had been proven successful by Dr. Edward Jenner (1749-1823) in Gloucestershire, England against cow pox in 1796. The concept of sanitation and personal hygiene being connected to health was only beginning to gain currency; in 1854, Dr. John Snow (1813-1858) traced the source of an outbreak of cholera, an acute intestinal infection causing diarrhea and vomiting that can quickly lead to severe dehydration and death, to a single infected public water pump on London’s Broad Street. Deducing that the water was tainted, the pump removed and within three days, the spread of the outbreak was stopped.

Two decades later, Dr. Robert Koch (1843-1910), a German physician, proved that anthrax, a disease common to cattle, sheep, horses, and goats in the area in which he lived, was caused by the microorganism anthrax bacillus, which had been discovered in 1850. This was the first time a disease had been linked to a specific bacteria, an idea which the French physician and research scientist Louis Pasteur (1822-1895) later expanded on in his research of the infectious disease rabies.

By the early decades of the 20th century, medical science had left the old ideas behind. The cause of disease was understood, even if treatment was still beyond its means. Doctors who half a century earlier might have moved from the dissection room to the operating theater without a stop in between to wash their hands, were now conscious of such hygienic practices as sterilization of medical instruments by high heat to kill microorganisms.

But, even by 1918, when Dr. Miner saw the first cases of influenza in Haskel County, the treatment of disease was still in its infancy. Doctors could diagnose an illness and try to make their patients comfortable, but there were precious few medications to alleviate symptoms, including aspirin and morphine, and less to actually cure diseases. So when case after case of an unusually intense and rapidly progressing influenza struck, swiftly killing dozens of formerly strong and healthy patients, there was little this country doctor, though a progressive man of science, could do except study the killer.

Dr. Miner had, of course, seen outbreaks of influenza before, but none as severe as this. He collected blood, urine, and sputum samples from his infected patients and scoured the medical literature for answers. Though the outbreak began to subside by March 1918, Dr. Miner’s concerns did not. He wrote to the U.S. Public Health Service’s weekly journal, Public Health Reports to warn of “influenza of severe type,” but his was the lone voice of warning on the possible outbreak of a virulent new strain of a deadly disease.

Since

April 1917, the U.S. had been involved in the war then raging across Europe.

Indeed, in expectation of entering the conflict, the country had been

mobilizing, enacting the draft in May 1918 and building military camps and

training facilities as fast as possible. Never before had so many men been

brought together in so tightly confined quarters in so short an amount of time.

But

as deadly as the European conflict was expected to be, there were those who

knew of an even deadlier threat facing America’s military forces, a threat

responsible for more deaths during wartime than combat: disease. Among those

sounding the warning were the army’s Surgeon General William Gorgas (1854-1920)

and Dr. William Henry Welch (1850-1934), the influential head of Johns Hopkins

University, the first modern medical school in America. Both men knew that

throughout history, not only had disease claimed more soldiers than had the

wars they fought, but that disease routinely and swiftly spread from armies to

civilian populations.

In spite of their records in the field of contagious diseases—Dr. Gorgas was responsible for implementing the sanitary conditions that halted the rampant spread of malaria in Panama and allowed for the completion of the Panama Canal at the turn of the century—their calls for measures to prevent the spread of disease among the growing army were given scant governmental attention, much less support.

Thus,

in early September 1918, the first cases of influenza (which, because it was

first recognized and reported upon in Spain, would become known as the Spanish

flu) were being seen at Camp Devens, near Boston.

Dr. Miner had sounded the first warnings. But before

the deadly disease could run its course in 1919, more American soldiers would

die from the flu than in combat, over one-fifth of the world’s population would

be infected, and as many as one hundred million people worldwide would die from

the disease that caused the most devastating pandemic in history.

Tags: 1918, flu, Great Influenza Pandemic, influenze, Paul Kupperberg, Rosen Publishing

Recent Comments